Module 13 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Multi-cultural perspectives:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Resources |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Resource 3

The Cultural Origins of Surfing

|

Source: The History of Surfing by Nat Young published by Palm Beach Press, 1983. |

Did you know that....

surfing originated in indigenous Hawaiian culture?

Captain Cook was the first European to witness surfing in action?

the first Australian to ride a surf board was a women?

Surfing is one of the world's most popular water sports. Today it is enjoyed by millions of people around the planet, but its roots lie in the ancient indigenous cultures of Polynesia. In Hawaii, surfboard riding is more than just a healthy pastime, it has been an integral part of cultural, political and religious life for thousands of years.

Most of what we know about early surfing comes from ancient chants that were handed down verbally from generation to generation. The Hawaiian scholar Samuel Kamakau wrote down the story of Umi and Paiea, two chiefs from the fifteenth century who were also fine surf riders:

`His name was Paiea, and he knew all the surfs and the best one to ride...It was a huge one which none dared to ride except Paiea, who was noted for his skill. Gambling on surfing was practiced in that locality. All of the inhabitants from Waipunalei to Kaula placed their wager on Umi, and those of Laupahoehoe on Paiea.

The two rode the surf, and while surfing Paiea noticed that Umi was winning. As they drew near a rock Paiea crowded him against it, skinning his side. Umi was strong and pressed his foot against Paiea's chest and then landed ashore. Umi won against Paiea and because Paiea crowded Umi against the rock with the intention of killing him, Paiea was roasted in an imu (oven) in later years when Umi became the supreme king of the Big Island.'

When Christian missionaries arrived in Hawaii during the nineteenth century, surfing went into decline and the practice nearly died out altogether. At that time even swimming in the ocean was regarded suspiciously by Europeans, and there was a general belief that outdoor bathing helped to spread the epidemic plagues of the Middle Ages. The missionaries strongly disapproved of surfing because they thought it was hedonistic, (or pleasurable for the senses), and a distraction from Christian

values. They forced the islanders to abandon their traditional practices, including surfing, and forcibly converted them to the Christian religion. Surfing became a form of cultural resistance or protest and was kept alive by a handful of people who continued to surf despite the attempts of the colonists to ban the practice.

|

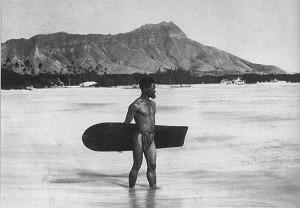

At the beginning of the twentieth century there was a rebirth of surfing at Waikiki on the island of Oahu. The man who took surfing to the United States was George Freeth, a Hawaiian of Irish and indigenous parentage who was California's first life guard, an innovator in surfboard design and a national hero for braving mountainous surf to save the lives of seven Japanese fishermen in 1908. Surfing rapidly caught on and Americans `discovered' Hawaii as a holiday resort. Locals were employed as `beach boys' to entertain tourists with their incredibly skillful manoeuvres such as surfing backwards, headstands and tandem with a dog. One of these local surfers was Duke Kahanamoku, who came from a large surfing family and became a champion Olympic swimmer and one of the greatest surfers in modern history. It was Duke who brought surfing to Australia, when he was invited to swim at the Domain baths in Sydney in 1915. He gave an exhibition of surfing at Freshwater on a board he built from sugar pine and astounded the crowd with his surfing prowess, including a tandem with local girl Isobel Latham - the first Australian to ride a surfboard. From that moment surfing grew in popularity and is now, after swimming, the most popular water sport in the world. |

`Hawaiian Surfer at Waikiki about |

Questions

- How do you think the missionaries and the Hawaiians had different ideas about the sea? Do you think the missionaries understood the significance of surfing in the culture of the Hawaiian people?

- How do you think the ban on surfing might have affected Hawaiian culture? What would have been the overall effect of the colonization process?

- Pretend you are a missionary who has just seen someone surfing for the very first time. Write a letter to a friend at home what you have just seen.

Resource 4

Multicultural Broome and the Pearling Trade

|

Sources: The Pearl Shellers of the Torres Strait by Regina Ganter, Melbourne University Press 1994 Australia; Then and Now by Garry Disher, Oxford University Press, Melbourne 1987; Images of Home by Effy Alexakis and Leonard Jariszewski, Hale and Iremonger 1995. |

Broome on the north-west coast of Western Australia is one of the most multicultural towns in the world and was built largely on a single marine industry - the pearling trade. It began as a colonial industry which flourished in the 1800s, Australia eventually becoming the biggest supplier of pearl and pearl shell in the world. Broome was Australia’s largest pearling town, supporting some 400 pearl boats or luggers and several thousand divers at its peak around the turn of the century.

Aboriginal people in northern Australia had been collecting pearls for

centuries when early colonists saw opportunities to further exploit this

‘untapped’ resource. Pacific Trading Companies set up business

in the Torres Strait Islands and the north of Australia which were based

on the colonial trading model. Workers were imported from Pacific Islands,

Malaysia, the Philippines and Japan to provide cheap labor for an industry

that ‘raided’ reefs rich in pearl shell and moved on elsewhere

when stocks were depleted. Because the work force was transient and indentured

they had no ownership over the resource and no stake in its conservation.

They lived and worked on shore stations managed by the companies and were

dependent on their employers for food and accommodation. Wages were minimal

and workers were often paid in rations of flour, sugar and tea.

From the very beginning the pearl trade was stratified along ethnic lines.

Local aborigines were almost excluded from the industry, and their employment

was restricted to the most unskilled areas where they had little say in

the management of the resource. They were ‘recruited’ for beche-de-mer

fishing and as shore based swimming divers under often brutal conditions,

sometimes they were even herded by police and sent to pearling fleets

in chains. Torres Strait Islanders were employed as deck hands and swimming

divers on luggers. With the introduction of dress diving, Japanese pearl

divers were recruited to skilled positions and the labor force became

even more hierarchical. As pearl shell became scarce, new recruits were

imported from the Philippines and Dutch East Indies and were paid minimal

rates per tonne of shell.

The workers received little financial reward and faced many dangers on

the job - there was constant risk of shark attack, injuries from sting

rays, drowning when hoses became tangled or broken and the infamous divers’

‘bends’. Concerns about abuse led to the introduction of restrictive

and protective legislation. However, the new laws were set up to meet

the demands of the pearl boat owners and their effect was to reinforce

inequalities which were justified on the basis of social Darwinist notions

of racial differences.

Japanese pearlers eventually became the backbone of the industry and introduced

technical developments such as the ‘half dress’ for greater

mobility. At the time the White Australia policy was introduced, there

was a lot of opposition to Asian migration and anti-Japanese sentiment

which culminated during the Second World War. By this time the pearling

market had collapsed due to the introduction of cultivated pearls and

plastic buttons which replaced demand for natural pearl shell. In the

1950s the Australian government sponsored the migration of sponge fishers

from the Greek Islands to revive the pearl industry and many of them stayed

on to establish their own fishing businesses.

Broome today is a very multicultural community, as evidence by the architecture,

street signs and the ethnic diversity of the residents themselves, many

of whom are descendants of these early immigrants who were involved in

the pearling trade.

Questions

• Look at a picture of an old ‘dress diving suit’. What does it remind you of? What would it have been like to work as a pearl diver in the early days?

• Why do you think so many people left their countries to join the pearling crews?

• How do you think the story of the pearling trade might be similar to other industries in Australia?

Resource 5

A Childhood by the Sea

‘When I was young we would go to the laguna for family celebrations,

the whole town would come, you know how it is... We’d buy fresh fish

directly from the fishermen, sometimes they’d barter for rice and

cigarettes. In the rainy season fish was expensive so we'd buy it beforehand

and preserve it in salt to eat during this time. When I buy fish I like

to know it's fresh. If the eye is clear, then you know it's fresh. ‘

Antoinette and Jeanette, Filipino migrants living in Melbourne.

|

Source: “Cultural Perceptions of the Coast Project, Inner Western Region Migrant Resource Centre (unpublished). |

‘Zeffirino’s father never got into bathing dress. He stayed in rolled up trousers and vest, with a white linen cap on his head, and never moved away from the rocks. He had a passion for limpets, the flat clams which stick to rocks and become with their very hard shells almost part of the stone. To prise them off Zeffirino's father used a knife, and every Sunday he would scrutinize the rocks on the headland one by one through his spectacled eyes. On he would go until his little basket was full of limpets: some he ate as soon as he gathered, sucking the damp bitter pulp as if from a spoon: the rest he put into his basket. Every now and again he would raise his eyes, let them meander over the smooth sea and call out : ‘Zeffirino ! Where are you?’

from Big Fish, Little Fish by Italo Calvino in The Picador Book of the

Beach, edited Robert Drewe, Picador Australia, 1993.

‘...in my memory of childhood there is always the smell of bubbling tar, of Pink Zinc, the briny smell of the sea. It is always summer and I am on Scarborough Beach, blinded by light, with my shirt off and my back a map of dried salt and peeling sunburn. In sight of the sea I felt as though I had all my fingers and toes. I was relaxed and confident.. the remainder of my life was indoor stuff - eating and sleeping and grinding through spelling lists, laps of the oval - but even from school I could see the bomboras breaking way out to sea on a high swell, there at the corner of my eye’

from Land's Edge by Tim Winton, Pan Macmillan, 1993.

Questions

• What memories do you have of the sea from your childhood?

• What sort of things did you do at the beach?

• Use these stories and your own experiences to present to the other groups (eg. using role play, dramatization, drawing etc.)

Resource 6

The Beach in Community Life

‘In my country it is very polluted. The coasts are the lungs of the city. The air is not polluted - it brings health to the people. In Australia the air is cleaner and everything is cleaner.

The beach in my country is a lovely happy place, there's music, people dancing and singing, places to buy food and the water is always warm. Spending time at the coast on weekends or holy days, it’s an old tradition. You can feel the ‘spiritual association’ to be with so many people and it is a different feeling. Beaches are lonely here (Melbourne), and there are no palms trees. In El Salvador there is a lot of happy people at the beach’

Emma, El Salvador

‘People have found that the sea is a source of health, a source of life... Above all, for the general public, it is a way of spending time without spending money, a way of living cheap...I think in all the Central and South American countries going to the beach is the major pastime for the people in summer and this produces these parties.... beaches in urban areas are very crowded during the holidays and people spend the whole day picnicking under the trees. Government services are very limited because of lack of economic means, the rubbish is all collected by hand, for example. Sewage from the city ends up not far from where people bathe. The rich people go to the resort beaches, where the councils have more money to spend on these services. You can go there for the day but they are very far and instead of paying $1 for a loaf of bread you pay $5.’

Luis, Uruguay

‘In the Philippines, if you want to go to the beach in a developed

area you have to pay an entry fee because most of the beaches are privately

owned. If you go for the day you hire a cottage, but for ordinary people

it is very expensive, so going to the beach is a special occasion. If

you live in the country you're lucky because the beach is natural and

less developed and you don't have to pay to visit there’

Gabby, the Philippines

|

Source: Cultural Perceptions of the Coast Project, Inner Western Region Migrant Resource Centre (unpublished). |

Questions

• What kind of role do you think the beach has in community life in Australia?

• How do you think the notion of recreation might be different for people in developing countries?

• Use these stories and your own experiences to present to the other groups (eg. using role play, dramatization, drawing etc.)

Resource 7

A Journey Across Seas

‘My family, just like many another family, went to find freedom - to find a bright future - and we escaped from Vietnam in February 1979, by boat at Longan and arrived in Malaysia after five nights and four days.

Walking up to the wooden boat about 22 metres long and 5 metres wide,

I did not know if I was happy or sad : I seemed to have no feeling. The

boat carried 350 people : it was suffocating. We could not move : we had

to sit with folded legs and drowsed. If you wanted to turn left or right,

or wanted to take something to eat, it was the most difficult job in the

world : people were everywhere - on the prow of the boat, people jostled

together.

The first morning came and we were advancing toward freedom, the sea was

calm and the colours of the sea were very dark, too, so you could imagine

that someone had poured blue ink into it. Inside the boat it was too hot,

and it smelled too much of someone who had vomited. I could not stay inside

anymore so I tried to go out on the deck and sat down there and looked

down at the sea. I felt homesick: I said to myself : ‘Goodbye Vietnam,

goodbye my beloved Grandmother, my relatives, goodbye all my good friends,

I go now and I do not know when I can come back to my country and visit

you, and my beloved country where I was born and grew up and where we

still have our home, our property which was made by my father with his

own hands and his mind and his life. Oh! Goodbye all of you, I hope I

can go back one day!...

My trip, just like the trip of any of my people was a trial, but not even

as much as other people : some of them died at sea, some lost a father,

a mother, some lost a wife: all the sorrowing things really happened to

us...Can any people in the world understand us, help us and save us?’

|

Source: “Why Must We Go?” by Hue Kim Chau, Richmond Girl’s School, Melbourne, in Australia : a Land of Immigrants by Beryl and Michael Cigler, Jacaranda Press, 1985. |

Questions

• How do you think an experience like this would your perception of the sea?

• How might it feel to be separated from your homeland by such a journey across seas?

• Use this stories and your own experiences to present to the other groups (eg. using role play, dramatization, drawing etc.)

Resource 8

Sense of Identity / Sense of Place

A common experience of many migrant people is the need to find their

own identity, to feel a sense of belonging in their new land. In a book

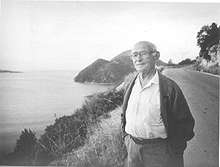

called Images of Home, Effy Alexakis and Leonard Janiszewski present photographs

and stories from the lives of Greek- Australians, many of whom have returned

to their homeland after long absences.

|

‘Once an individual had migrated, their identity and relationship

with their country of origin can never be the same. Some have great

difficulty deciding where to settle, uncomfortably spending their

lives searching for an ideal between two countries.’ Jack Morris (Zaharias Moraitis) migrated from the island of Ithaca in 1924. ‘I remember when I first was coming here to Greece, after fifty odd years, when I first went to my village, St. George Village, and when I saw the place, really, I thought, God’s in this land! .... What beautiful scenery.. Naturally, wherever you're born, you like it, no matter how small or big it is’ |

|

Source: Images of Home by Effy Alexakis and Leonard Janiszewski, Hale and Iremonger, 1995 |

Questions

• What is your connection with the place you were born or grew up?

• Do you have a special memory that you associate with home? (eg. a secret hiding place, a favourite view, a hidden pathway, a memorable event)

• Is there a particular image (smell, or sound) that reminds you of home?

What does it feel like to go back there after a long time away?

• Does your image of home affect how you see other places?

• Imagine a place where all the animals and plants are strange and unfamiliar. Draw a picture of what you would find there.

• You arrive in this place after a very long journey. You cannot go back because your home has been destroyed by a great fire. How do you feel when you first arrive in this new land?

• If you could take just three things to remind you of home, what would you chose? (They have to be small enough to fit in your suitcase!)

• The place you are visiting is very different and you want to explain to your new friends what your home looks like. What words would you use to describe your home environment? What natural objects from home would you chose to show them?When the first British settlers came to Australia they found the environment strange and unfamiliar. Many of the plants and animals they encountered were unlike anything they had ever seen (imagine their surprise the very first time they saw a kangaroo!) The climate was different, even the sky and the light from the sun was somehow not the same. They tried to recreate a feeling of home by bringing with them plants and animals from their homeland.

• Can you name some of the animals that were brought to Australia from Britain? What did the settlers use them for? Why do you think they didn't use the native animals for food and as pets?

• How does an English forest look different to the Australian bush? Can you think of any places near where you live that have plants and animals from England? How did they get there?The animals that were brought over from Europe were used as pets or farm animals. The plants were used in gardens or as crops to eat. Many of these plants and animals ‘escaped’ into the bush and became wild. Their numbers grew quickly because they did not have any natural predators or parasites in their new environment.

• Can you think of any ‘escapee’ plants that have become weeds? What about animals? What do you think happens to the native plants and animals when the introduced species are so ‘successful’?

• What effect have introduced people had on indigenous people in Australia?