Origin of animal symbols

Animals are a common inspiration for symbols in every society. For Aboriginal societies, whose economies were traditionally based on hunting and gathering wild foods, animal symbols were based on wild animals. Incorporating predators like sharks into religious symbolism might seem unusual in Western societies, but it is not really so strange; we continue to view certain predators as representing positive qualities like strength (the bear) and bravery (the eagle). For many coastal Aboriginal peoples, certain sharks and rays have similar positive associations and symbolic value.

Sharks and rays as resources

Elasmobranchs are highly symbolic in Aboriginal society and they are also valued as a source of food and raw materials. In Aboriginal thought, supernatural creator beings created the landscape and bestowed culture on mankind. Various sharks and rays were placed in the world by the ancestors to provide food for their descendants. This link between the ancestors, food species, and mankind is revealed through sacred signs in the landscape. Aboriginal hunters know when sharks and stingrays are “fat” and ready to be harvested when certain plants bloom–these are known today as calendar plants. These flowers are signs from the ancestral creators that a food species has been added to the menu for another season.

Traditionally, indigenous peoples did not share the Western notion of environmental conservation. They believed that food animals were released into the landscape by the ancestors as needed, so long as proper relations were maintained with them through ceremony, art, and song. However, use of animal species was controlled by laws established by the ancestors during the creation period.

As a result, most food species were only harvested seasonally, like when the calendar plants were in bloom. If hunters harvested animals out of season, they could be punished by the clan responsible for maintaining ritual relations with that species. These ancestral laws served to assure a steady supply of sharks and rays every year without causing population collapses.

Sharks and rays were also traditionally used to manufacture a variety of tools, weapons, and implements. On Groote Eylandt, for instance, the toothy snout of small sawfishes was sometimes used as a hair comb. Elasmobranch vertebrae, intriguing round spool-shaped discs, were strung as beads to make necklaces. Shark teeth were utilized to make carving implements and rough shark hide was sometimes used like sandpaper. |

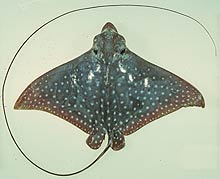

Eagle ray (Aetobatus narinari)

(© CSIRO Marine Research)

Sawfish (Pristis clavata)

(© CSIRO Marine Research)

Shovelnose ray (Rhinobatos typus)

(© CSIRO Marine Research)

|